Jim wrote about his thoughts on the most important advancements in educational technology. I think he’s onto something – the exact tech isn’t important. Nor are the logos on the shiny things we build and/or buy. My personal stance is that we’ve seen 2 major changes on our campus – neither of which are directly related to specific technologies.

- Human-scale technologies

- Distributed, coordinated, domain-specific community support

The first shift is nothing new – it’s also not constant or consistent. It’s about individualized ownership/control/access to technologies. Some new tools are cheap enough that people grab their own copies – even gasp without asking permission, or even notifying anyone. Some tools are good enough that The University grabs a few copies and hands them out more freely for people to do stuff. I’ve seen people do things with creating online resources for their courses that was simply not possible even a few years ago – and even if technically possible, involved the need to spin up projects, find funding, management, designers, etc…. Now, an instructor can sit at her computer and create really good resources for her courses, on her own, without needing to ask permission. And students can do the same. That’s a fantastic shift.

We’ve been doing things in my group to help with that – we’re setting up a Faculty Design Studio, to give people a place to come work with higher-end tools. We’re ramping up a “tech lending library”, so people can sign stuff out, without needing to go through Project Management or funding requests. Want to play with a GoPro camera to record something for your course? Go for it. Need a tripod, microphone, camcorder, lights? Sure thing. Keeping technology available at human scale is important. It’s more than Enterprise Platforms and [Learning|Research|Administration] Management Systems.

We’re also changing how institutional programs are being run. Our Instructional Skills Workshops involve participants recording themselves presenting or facilitating. In the Olden Days™, that involved a big video cart, with microphones, cameras, mixing boards, DVD recorders, CRT monitors, etc… and was a Big Deal to set up. Now, we have a set of Swivl robot camera mounts, some iPod Touch handheld video recorders, and a tripod. Done. Videos get uploaded to Vimeo1, and it’s all faster, easier, and better than what we did before. And instructors are signing the Swivls out to do similar things for their own courses. Great stuff.

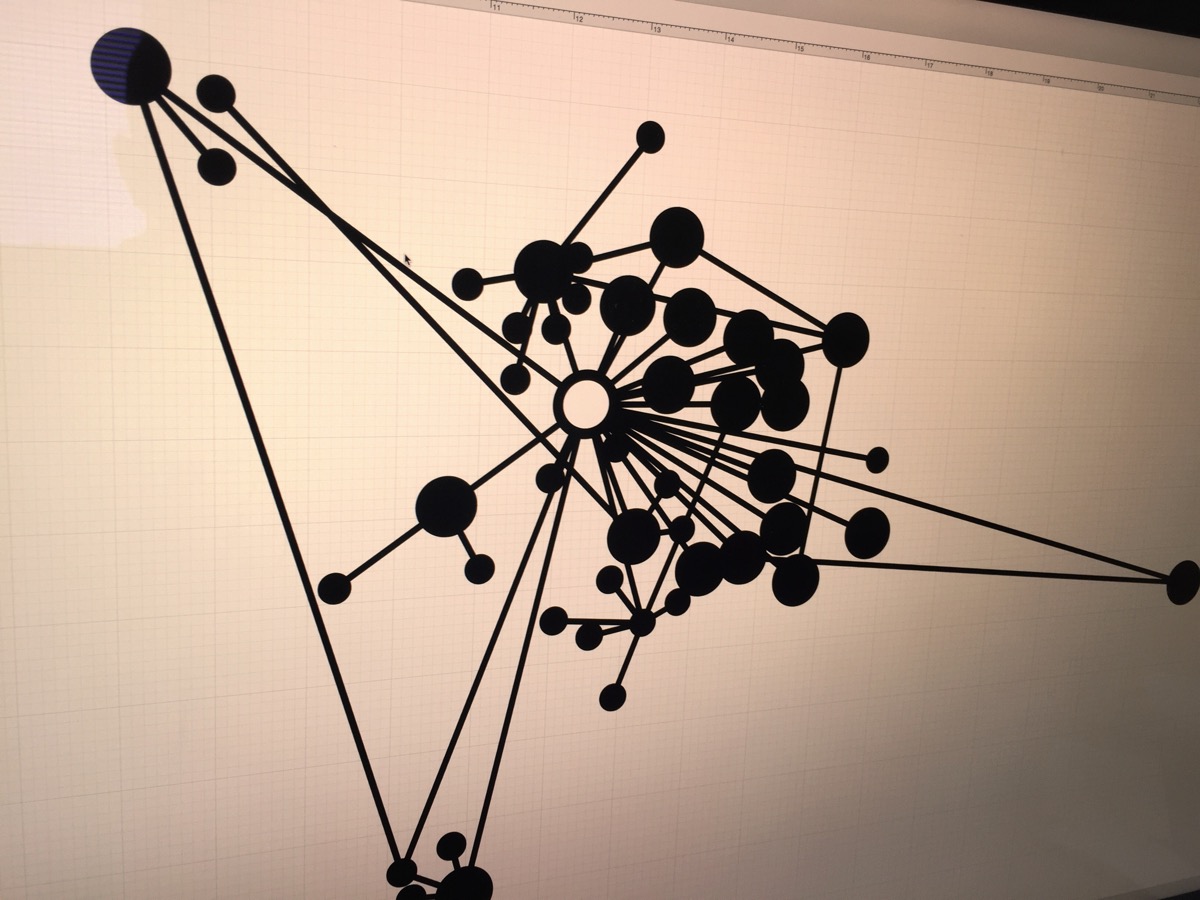

The second shift is probably the more important one, though. Distributed, coordinated communities of practice to support instructors who are designing their courses and integrating learning technologies. We’ve moved from a centralized model – where everyone had to come to The Big Department In The Middle™ to get “help” to fix their courses. That wasn’t great for a few reasons – it can’t scale, without dozens of staff members in TBDitM™ – but also, it positions the support for technology integration as some Other. Something bolted on by other people outside of an instructor’s faculty or department. Something foreign, extra, separate. Superficial.

The community of practice shifts the support model into being native in each faculty and department. With domain-specific understanding of the pedagogies used in each context, and of the activities that make up the learning experience. And of the technologies that enable, enhance and extend these activities. We had this, informally, before – but isolated pockets of in-context support were not able to benefit from what people had learned or tried in other contexts. So, intentionally designing the central portion of the support community as a coordination hub to enable people across campus – NOT as a “come to us in The Middle and we’ll fix your stuff”, but as “hey – let’s come together to learn about what we’re all doing, and how we can share that to make it all sustainable and meaningful for everyone.”

That’s where the magic is. Coincidentally, I’m currently looking to hire the person who will act as our coordinator/collaborator/cruise-director for this distributed community of practice.

- until we eventually get a campus video platform set up – 4 years and counting on that… [↩]