I don’t usually have to put an explicit disclaimer on posts, but here goes. I’m not writing this in any official capacity, my university hasn’t approved the message. YMMV. IANAL. YHBH. etc…

I was at a presentation by Dr. Krishnaswamy Nandakumar on the impact of technology in education, and it triggered some thoughts on MOOCs. I’d been avoiding thinking (or writing) about them, because the hype just seemed silly and pointless. But, combined by a recent nudge by Kate Bowles, I think it’s worth writing it now.

Dr. Nandakumar gave a really interesting presentation about how he shares all of the materials for his courses, including recording the lectures and putting them on YouTube for use by his students as well as anyone else who find the topic of chemical engineering interesting. He gets lots of feedback from people who appreciate him sharing his stuff, and he is passionate about the power of technology to extend access to education to anyone who wants it. He spent a fair bit of time talking about content production, but made it clear that the real value he sees is in making it possible to connect people in the context of working through problems while learning.

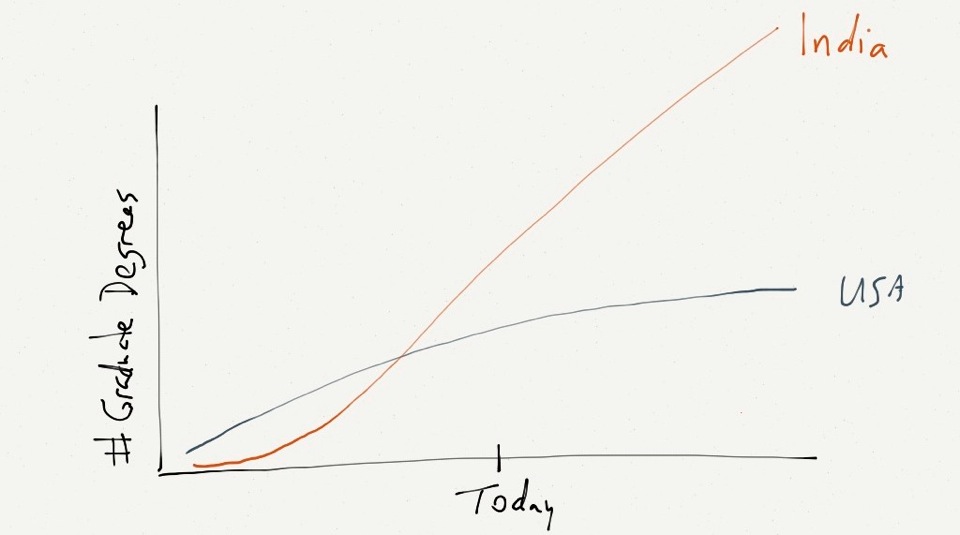

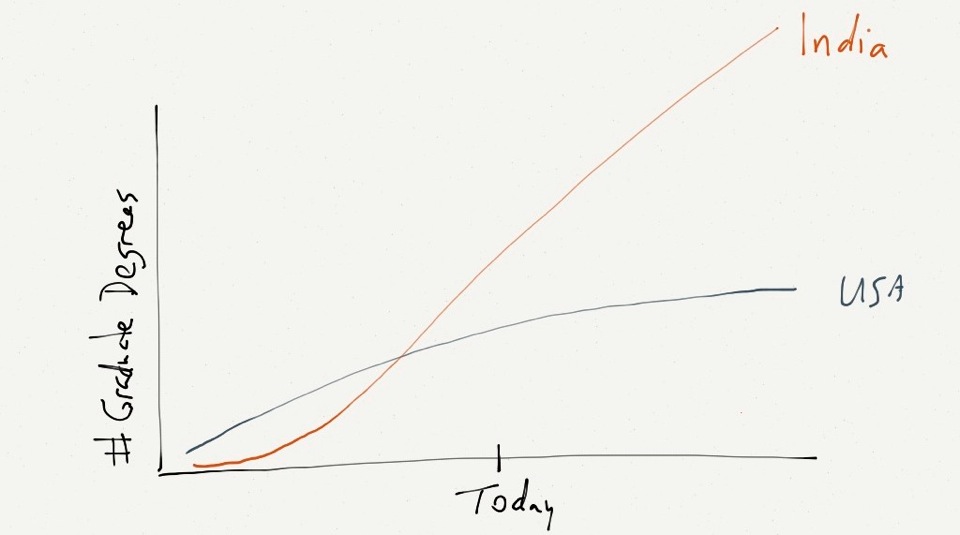

And he talked about MOOCs quite a bit, including a slide that resembled this: (but with actual numbers and citations etc… – none of which were used in creating my version of the slide from memory…)

He was talking about how the number of degrees granted, and specifically graduate degrees, is higher in India (and the other BRIC ) countries than in the US and Canada. He described the role of MOOCs here, to lower the cost of getting a degree in order to keep North America competitive with BRIC nations who are building hundreds of post-secondary institutions in order to crank out more graduates. The idea is that if we lower the cost of getting a degree, that more people will earn degrees here, keeping us competitive with the BRIC nations that are pumping out significantly more graduates than us.

But. Lowering the cost would apply across the board. It would make it easier for a higher percentage of BRIC citizens to earn degrees as well. If anything, the delta between Indian (and BRIC) and North American degree granting would increase. So it’s not about a competitive advantage, or even about keeping up with other nations. The mathematics of populations and demographics make that a losing battle, and one that can’t really be fought anyway. BRIC nations have significantly more people than North America, so after a certain point, there is physically no way for us to produce as many graduates as they can.

OK. So MOOCs aren’t about maintaining a competitive advantage in number of graduates. Maybe they’re used as marketing tools? This seems to be the explicit purpose of many initiatives – raise the profile of an institution and get buzz in the Media because of MOOC offerings. Get articles in the Media describing 100,000 students in a single course. And since it’s a marketing investment, that’s all they need in order to succeed.

But, I would suggest there’s something else going on. Maybe explicitly, maybe implicitly. Maybe subliminally. Given that we will never be able to catch up to the sheer numbers of graduates, and that marketing may be of limited value once buzzword saturation has been achieved, what else is driving the MOOC initiative? I propose that it’s fear.

First World Big Fancy Schools are afraid of losing control of the market. If an institution in India can draw significantly more students, graduating significantly more PhDs, and eventually draw significantly more funding than a Harvard or Stanford or MIT can, how do the Big Fancy Schools stay relevant?

By controlling the curriculum and putting themselves at the top of the educational food chain. By creating resources to extend their reach and values into other institutions. By letting other institutions build programs based on the resources of the Big Fancy Schools, and by declaring themselves to be subservient to them in the process. The value proposition becomes “You’d rather go to a Big Fancy School, but since you can’t afford that, you can get some of that by coming to Provincial Institute of Technology and getting credit for the same courses you’d get at a real Big Fancy School.”

The BFSs maintain their position as the alpha dogs, controlling other institutions through their influence, and shaping the values of educational systems around the world.

This is cultural imperialism, and it’s not a new concept. Leigh Blackall has been writing about this for years.

I’m not saying MOOCs are bad, or that the intentions of MOOCing institutions are evil. They mean well. They likely aren’t intending to explicitly assert dominance over lesser institutions. They’re probably doing the MOOC and OER things for All of the Right Reasons – to share, and to make things better for everyone. But there’s another side to that coin. Those who have the resources to share their things are able to shape things in ways that are more difficult for the recipients to do.

It’s a risky gamble for the recipients – for an institution to base their programs on MOOC courses, they essentially defer to another institution. They lose full control and autonomy over their curriculum. They become, on one level, agents for the First World Big Fancy Schools. All it would take would be for the First World Big Fancy Schools to come up with a way to charge MOOC participants a small amount directly and grant them accreditation themselves, and the recipient institutions become redundant.

I’ll be very interested to see MOOC programs coming out of BRIC nations, or Africa, or South America, rather than seeing the flow going from The First World and into Lesser Countries That Need to be Saved.

Anyway.

End of rant. Hopefully the last thing I write about MOOCs…