This is where I go out on a bit of a limb, but I think it’s important to share this kind of info to see if it’s on the right track, too ambitious, or not ambitious enough.

Basically, the last year has been one of constant change in learning technologies at the UofC. We changed LMS, from an antique version of Blackboard, to the latest version of Desire2Learn. We replaced Elluminate with Adobe Connect. We rolled out Top Hat as the campus student response system. It’s been a lot of things changing, some while the academic year was under way. I’m hoping we have these things stabilized by the end of the Fall 2014 semester, so we can move on to more interesting things.

We have had difficulty in keeping our key learning technologies up to date over the years, in a kind of digital parallel to deferred maintenance on our facilities. Then, when we reach a crisis, we have to react and strike Urgent High Priority Projects to enable massive change to respond to impending technology failures. We need to get past that reactive mode, which keeps our resources tied up in emergency projects, and into a more proactive mode that is forward-looking, so that we’re able to plan ahead rather than panicking about averting imminent disaster.

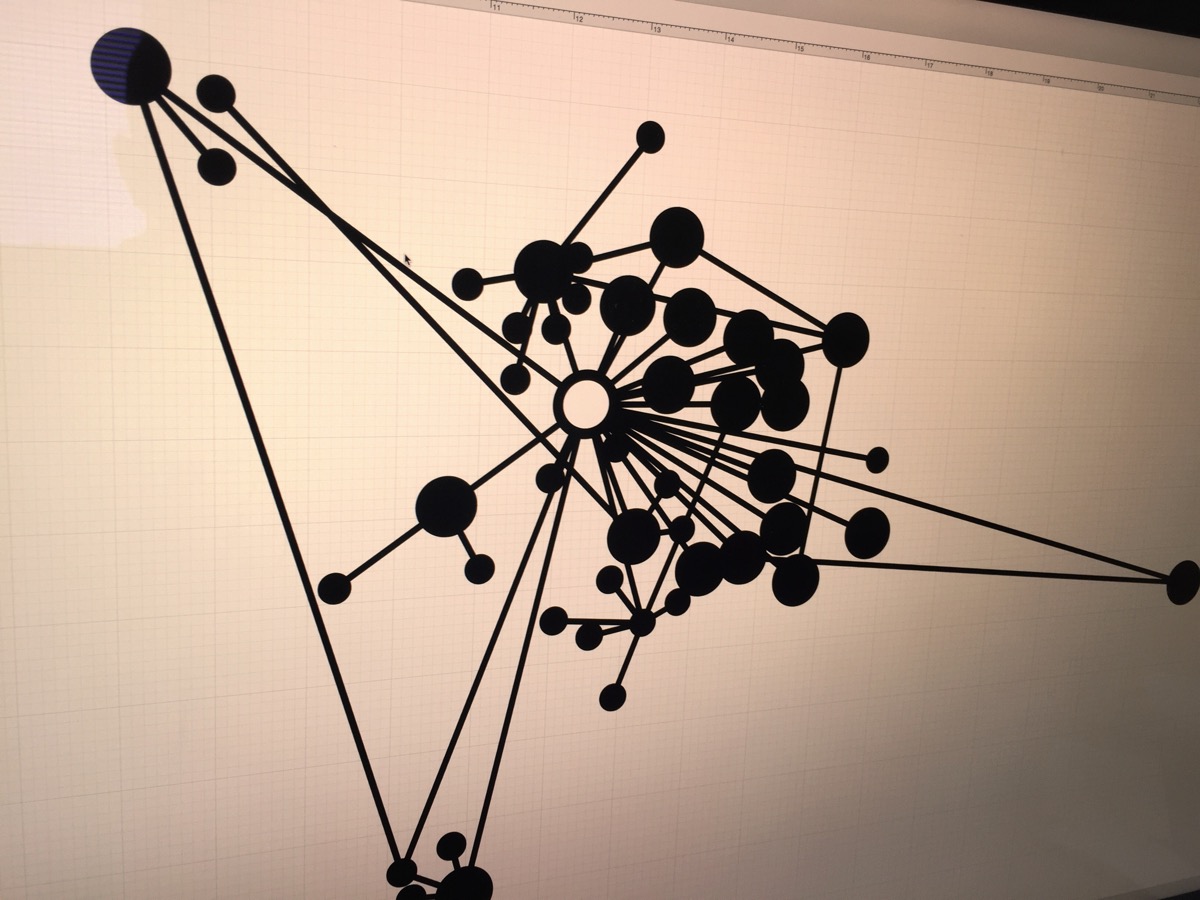

As a university, we offer a set of common tools that form up the core learning technologies platform. This is important, because it provides a common starting point for all 14 faculties and various service units. If they can start with a common set of tools, we can provide some cohesive support and enable people to get up and running. It provides a consistent experience for students, so they don’t have to learn one LMS for a class in Sciences, and a different one for a class in Arts, and a different one for one in Kinesiology, etc…. That consistency is downplayed, but it is incredibly important.

Students are under a pretty extreme level of pressure to succeed. They face rising costs, crushing debt, and more competition than ever before. If we can provide them with a consistent experience, they spend less time learning the tools and more time engaging each other and doing more interesting things.

Also, we have students whose success depends on this consistent experience – anyone that uses a screen reader to support their visual challenges will tell you that inconsistent interfaces essentially destroy the learning experience for them, as they have to battle with various navigation models and learn to find things in each environment.

The University of Calgary’s common learning technology platform currently consists of:

- Online Tools

- Desire2Learn

- Adobe Connect

- Top Hat

- UCalgaryBlogs.ca

- wiki.ucalgary.ca

- Classroom Tools (classroom podium software stack)

- SMART Notebook

- MS Office

- various media players

- various web browsers

- Skype

These are common tools that are centrally funded, and are available for use by every instructor, student, and staff member in our community. They provide various levels of flexibility, which cover the most common use cases (and UCalgaryBlogs.ca even lets you pick various themes and enable plugins to really customize your site as needed). And UCalgaryBlogs.ca and wiki.ucalgary.ca probably wouldn’t have been considered part of the core common learning technology platform before I started my new role and basically started telling everyone that that’s what they were.

But, these tools don’t cover all common needs. We still need to add a few tools. The most urgent needs are for video hosting and survey management.

Video hosting is important because we currently don’t have a place where we can say “hey. you need to share a video? just use this…”. Today, individuals have to spin up their own YouTube, Vimeo, Flickr, or other accounts and publish their videos there. Which works, but what happens when an instructor leaves the university? The videos they published to their accounts on various services disappear. We have no way to provide support for these services. Students, again, have an inconsistent experience (why does video from my Math course work on my iPad, while my Chem course videos don’t?). At the moment, the only campus platform for hosting videos is a static webserver. So, 500MB video files are uploaded to a server, students are expected to download the video and install whatever video player is required (is it MP4? Will that work in QuickTime, or do I need Windows Media Player? Can I play a WMV file? etc… and we still have courses with Real Media files. Yeah.

So, by adding a video hosting service to our common platform, instructors and students can host videos in a place that’s managed and consistent, and will be able to know that videos will work on whatever device they use, and won’t disappear when a prof moves to another institution.

Similarly for survey management. We currently rely on individuals to spin up their own Survey Monkey or similar account, learn how to use it (there are many many online survey platforms that are used), and pay for the pro account so you can export your full data set. This adds up quickly. If we provided a campus survey platform, individuals wouldn’t have to pull out their credit cards, and we’d be able to manage the data and provide a level of support that isn’t possible otherwise.

OK. So we add video hosting and online surveys to the common learning technology platform. That provides the starting point for all faculties to build from. But it still won’t cover unique needs – we have 14 faculties, each with signature pedagogies, and it’s just not realistic to assume that their unique needs can be fully met by a handful of campus-provided common tools. How do we provide a common set of tools and support innovation and unique requirements?

Departments often manage their own platforms – our Faculty of Medicine is involved in an open source consortium to build and maintain an online platform tailored to their needs. They also get to manage the servers and software required to run that platform. Other faculties use other platforms, and are able to have dedicated servers managed by Information Technologies in our campus datacentre, but each one is essentially a standalone project, requiring separate dedicated resources to maintain and monitor the server and its software.

What if we were able to provide something like the Reclaim Hosting model on campus? That would give individuals access to host whatever software they need, mostly through the one-click installers built into CPanel, while running the whole thing within the campus datacentre so that everything is properly managed and backed up. Again, this is stuff that’s possible now, by having individuals go to GoDaddy, MediaTemple, iWeb, or any of a long list of hosting providers where they can set up whatever they want. But, they have to find a good provider. They have to learn the unique way of managing the software on that provider’s platform. They have to remember to pay the annual fee charged by the service provider. And they need to back their stuff up. That’s a lot of points of failure. We need to provide a more streamlined way of supporting this kind of innovation, so they’re able to focus more on the innovation and less on the management of the service.

I think this is where we need to go as a university. We need to provide the best core tools as a common platform. We need to provide consistency while not stifling innovation. And we need to provide support for innovation, exploration, and truly unique use cases.

So, my visionary plan for campus learning technologies is to finish stabilizing things by the end of the Fall 2014 semester (which means before Christmas 2014), adding in the missing pieces to make sure we have a really solid core platform. And then, to be able to start working on more interesting things, including planning out what would be required to implement a Reclaim Hosting service on campus.